Whatever our motivation, nothing made pulling a 150lb sledge up a glacier from the coast any easier. But when in mid-July we arrived at our first camp, we had a genuine feel for our location. 70 miles by boat from the airstrip, then 35 miles from and 1350m above the snout of the glacier. Over the expedition, we spent 9 days ski touring with pulks, moving between a series of camps where we stayed to climb in the area. And it was well worth the sweat. 120 miles of skiing through untouched mountains and experiencing a wide range of conditions. Watching, feeling and even hearing glaciers at work. Yawning crevasses - hard ice surfaces - ploughing through powder snow... [ Top ]

Whatever our motivation, nothing made pulling a 150lb sledge up a glacier from the coast any easier. But when in mid-July we arrived at our first camp, we had a genuine feel for our location. 70 miles by boat from the airstrip, then 35 miles from and 1350m above the snout of the glacier. Over the expedition, we spent 9 days ski touring with pulks, moving between a series of camps where we stayed to climb in the area. And it was well worth the sweat. 120 miles of skiing through untouched mountains and experiencing a wide range of conditions. Watching, feeling and even hearing glaciers at work. Yawning crevasses - hard ice surfaces - ploughing through powder snow... [ Top ]

It would take a book to describe everything we did. So sparing that, here are a few of the tastiest morsels; beginning with the third climb of the expedition. At the time, I couldn't see a better climb on a better mountain, and 35 days and 25 routes later, it remained one of my favourites. The mountain was impressive, of course unclimbed, and it looked hard - rock climbing all the way. It really got the juices flowing and we got ourselves up 2 hours earlier than usual to tackle it. This was a good move as the glacier surface was still icy and our skis skidded the 3km across to the base of the south face. There we left skis and changed into plastic boots and crampons for a brief snow climb. But soon the ascent moved to rock, and we left all equipment for snow climbing in a stash - it would mean substantially lighter ruck sacks for the rest of the day. The lower sections of the face were loose, but not too steep. We moved together over this ground, with the main danger being rope damage. Soon it became increasingly contrived to maintain a scrambling line, and we decided to get stuck-in to the main business of the day: Pitch after pitch elevated us up a clean, broken ridge. To start, the climbing was easy, but then we found more interest, and as predicted by telephoto-lens inspection we came to the crux section.

It would take a book to describe everything we did. So sparing that, here are a few of the tastiest morsels; beginning with the third climb of the expedition. At the time, I couldn't see a better climb on a better mountain, and 35 days and 25 routes later, it remained one of my favourites. The mountain was impressive, of course unclimbed, and it looked hard - rock climbing all the way. It really got the juices flowing and we got ourselves up 2 hours earlier than usual to tackle it. This was a good move as the glacier surface was still icy and our skis skidded the 3km across to the base of the south face. There we left skis and changed into plastic boots and crampons for a brief snow climb. But soon the ascent moved to rock, and we left all equipment for snow climbing in a stash - it would mean substantially lighter ruck sacks for the rest of the day. The lower sections of the face were loose, but not too steep. We moved together over this ground, with the main danger being rope damage. Soon it became increasingly contrived to maintain a scrambling line, and we decided to get stuck-in to the main business of the day: Pitch after pitch elevated us up a clean, broken ridge. To start, the climbing was easy, but then we found more interest, and as predicted by telephoto-lens inspection we came to the crux section.  The corners and ribs linking ledges and pedestals ran out below steep smooth rock. Initially twin cracks formed the only line, then at 20m, a ledge. Getting off this was over an awkward looking bulge, and then above - flutes. Rock boots were donned, nervous banter exchanged, and I started up. In my opinion, this is climbing at it's most rewarding. Knowing that this is the only line on a route to a previously unclimbed mountain, and that I might not be able to climb it. Then after several moves, a quiet confidence built, and as I climber higher still this turned into outright delight. Technically the section was beautiful moderate grade climbing that would gain classic status on any British crag, but this was multiplied by the Greenland setting. Remote, Arctic, exposed, virgin. Richard followed past me with another stunning pitch which involved an outrageous swing out and pull over an exposed flake. And above, there was even more. After a while we came to a section of traditional Arctic rock, shady and hideously loose. But having conquered this, we were on the main ridge of the mountain, with only a couple more pitches of traversing and thrutching to reach the summit.

The corners and ribs linking ledges and pedestals ran out below steep smooth rock. Initially twin cracks formed the only line, then at 20m, a ledge. Getting off this was over an awkward looking bulge, and then above - flutes. Rock boots were donned, nervous banter exchanged, and I started up. In my opinion, this is climbing at it's most rewarding. Knowing that this is the only line on a route to a previously unclimbed mountain, and that I might not be able to climb it. Then after several moves, a quiet confidence built, and as I climber higher still this turned into outright delight. Technically the section was beautiful moderate grade climbing that would gain classic status on any British crag, but this was multiplied by the Greenland setting. Remote, Arctic, exposed, virgin. Richard followed past me with another stunning pitch which involved an outrageous swing out and pull over an exposed flake. And above, there was even more. After a while we came to a section of traditional Arctic rock, shady and hideously loose. But having conquered this, we were on the main ridge of the mountain, with only a couple more pitches of traversing and thrutching to reach the summit.

At 4pm we summited. No one had been there before, no one had seen that view. Seven and a half hours of AD+ climbing needed to get there. We all felt like a members of a club, a very exclusive club - it was a magical feeling. But the top of a mountain is by no means the end. There was no cable car down, nor a walk off the back, and no guidebook to reassure us on the descent. We now had to reverse the whole route. Down climbing, abseiling, down climbing. And as we did so, the sun became lower, giving the scenery a golden tint, and a real sense of space in the otherwise crystal clear air. By the time we returned to our skis, the sun had dipped just below the horizon, and the glacier surface was again icy. Despite the early start, we were using the 24hr Greenland day light - we arrived back at camp at mid-"night". [ Top ]

At 4pm we summited. No one had been there before, no one had seen that view. Seven and a half hours of AD+ climbing needed to get there. We all felt like a members of a club, a very exclusive club - it was a magical feeling. But the top of a mountain is by no means the end. There was no cable car down, nor a walk off the back, and no guidebook to reassure us on the descent. We now had to reverse the whole route. Down climbing, abseiling, down climbing. And as we did so, the sun became lower, giving the scenery a golden tint, and a real sense of space in the otherwise crystal clear air. By the time we returned to our skis, the sun had dipped just below the horizon, and the glacier surface was again icy. Despite the early start, we were using the 24hr Greenland day light - we arrived back at camp at mid-"night". [ Top ]

Well lucky us! 8 weeks of stunning adventure. But it wasn't all like I describe above. We had our share of bad weather, and very bad weather. Three blizzards of note, each lasting 2 days, and each burying our tents repeatedly. Lying in the tent, it was hard to remember the other Greenland of blue skies and inspiring peaks. My mind was more concerned with: Why have I eaten tomorrow's chocolate ration already? Why can't I warm my feet up? and persuading my bladder that I don't need to go to the loo! After 5 days solid climbing, it was at first a relief to just lie there - letting fatigue sleep away. But it soon turned to frustration, and then boredom. One morning I remember waking to find it everything was quiet, no flapping nylon - peace. "The blizzard's stopped", I thought to myself "what a relief, dry socks by lunch time". Then I wriggled my head out of my bivibag and into a damp gloomy tent, my heart sank. It was quiet because we were completely buried in snow. At this point my bladder realised it could raise hell with me, as it would take a good 10 minutes to get all my foul weather gear on and dig my way out. And it really does take 10 minutes. You don't go out until the last gaiter velcro flap is closed, mitt on, and face guard in place. To do otherwise is to let the blizzard in - anywhere there is an opening it manages to get in. As I shovelled the last block of snow away from the door of the tent, and popped my head up above the new surface, I found that the wind and snow had in fact stopped. The blizzard was over and we could begin a day of digging out, drying and mending. To start with there were the other tents, only a few square feet of Richard's tent was visible. And inside it's trapped occupants were also desperate to get out and go to the loo.

Well lucky us! 8 weeks of stunning adventure. But it wasn't all like I describe above. We had our share of bad weather, and very bad weather. Three blizzards of note, each lasting 2 days, and each burying our tents repeatedly. Lying in the tent, it was hard to remember the other Greenland of blue skies and inspiring peaks. My mind was more concerned with: Why have I eaten tomorrow's chocolate ration already? Why can't I warm my feet up? and persuading my bladder that I don't need to go to the loo! After 5 days solid climbing, it was at first a relief to just lie there - letting fatigue sleep away. But it soon turned to frustration, and then boredom. One morning I remember waking to find it everything was quiet, no flapping nylon - peace. "The blizzard's stopped", I thought to myself "what a relief, dry socks by lunch time". Then I wriggled my head out of my bivibag and into a damp gloomy tent, my heart sank. It was quiet because we were completely buried in snow. At this point my bladder realised it could raise hell with me, as it would take a good 10 minutes to get all my foul weather gear on and dig my way out. And it really does take 10 minutes. You don't go out until the last gaiter velcro flap is closed, mitt on, and face guard in place. To do otherwise is to let the blizzard in - anywhere there is an opening it manages to get in. As I shovelled the last block of snow away from the door of the tent, and popped my head up above the new surface, I found that the wind and snow had in fact stopped. The blizzard was over and we could begin a day of digging out, drying and mending. To start with there were the other tents, only a few square feet of Richard's tent was visible. And inside it's trapped occupants were also desperate to get out and go to the loo.One of the things that makes a blizzard so unpleasant is the 7 x 3 x 4 foot space you're confined to. You feel trapped and cocooned. So, at the next camp, I took the first opportunity to spend a day digging an underground palace, where we could all gather, cook, stand upright, and forget about drifting snow. It really did take a day to build, and although I tried to consecrate it "The Chapel" (on account of the fine alcove architecture), "The Grouch Pit" was the name that stuck. A snow cave looks idyllic, but in reality it is cold, dark and also when cookers are on, wet. Not conditions where cookers and cooks perform at their best. Cooking gets slower, food quality rapidly falls off, cook gets in a foul mood. Then arrive the hungry troops, unaware of the problems, offering comments like, "um, this tastes like shit", and "mind if I leave mine on the snow to warm up?" - humour failure is imminent. But as I suspected, after all that work, we never had another blizzard. However a day of digging was a price worth paying for fine weather. [ Top ]

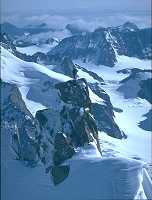

We were regularly making first ascents now. It was becoming routine. Knocking off 1800-2200m peaks by classic lines. Great fun, but these weren't the peaks in the area. How could they be? By definition there can only be one or two truly dominating summits in any region. But by our fourth camp we were under the flanks of "2100m" a twin summit mountain that truly did dominate. It was our top objective, and it merited another early start. To add to this mountain's domination in height was it's shape. It had that indescribable something that attracts the mountaineer. From all sides it seemed symmetrical and surrounded by extensive steep rock and snow faces. I did not fancy anything other than the easiest line. This started on skis, below the eastern flanks in a secondary glacier only 1 mile wide. We put skins on the base of our skis and skied up, and up, and up. The slope was steep for skiing, and on the limit of friction for our skins, but it was giving us a real height boost. After 1˝ hours we reached the top of this glacier, and a sharp col with panoramic views south. We could now see most of the ridge to the summit, and to our delight it looked simple. Indeed, most of it was, mainly snow climbing until 300 feet below the southern summit. Simple was how it seemed, but by now we were completely comfortable with 45o snow slopes that curved away under the front points of our crampons to leave nothing for 3000 feet - this was everyday and no more frightening than driving on a motorway. So far this route was well within our capabilities. But such a magnificent peak could not be just an easy snow plod, and the final 300 feet didn't disappoint. The line steepened and became confined to a gully until eventually the snow finished. The crux was escaping this gully, now on rock. It was a traverse across a blank slab via a break only big enough for feet or hands. But having done this the top was in sight.

We were regularly making first ascents now. It was becoming routine. Knocking off 1800-2200m peaks by classic lines. Great fun, but these weren't the peaks in the area. How could they be? By definition there can only be one or two truly dominating summits in any region. But by our fourth camp we were under the flanks of "2100m" a twin summit mountain that truly did dominate. It was our top objective, and it merited another early start. To add to this mountain's domination in height was it's shape. It had that indescribable something that attracts the mountaineer. From all sides it seemed symmetrical and surrounded by extensive steep rock and snow faces. I did not fancy anything other than the easiest line. This started on skis, below the eastern flanks in a secondary glacier only 1 mile wide. We put skins on the base of our skis and skied up, and up, and up. The slope was steep for skiing, and on the limit of friction for our skins, but it was giving us a real height boost. After 1˝ hours we reached the top of this glacier, and a sharp col with panoramic views south. We could now see most of the ridge to the summit, and to our delight it looked simple. Indeed, most of it was, mainly snow climbing until 300 feet below the southern summit. Simple was how it seemed, but by now we were completely comfortable with 45o snow slopes that curved away under the front points of our crampons to leave nothing for 3000 feet - this was everyday and no more frightening than driving on a motorway. So far this route was well within our capabilities. But such a magnificent peak could not be just an easy snow plod, and the final 300 feet didn't disappoint. The line steepened and became confined to a gully until eventually the snow finished. The crux was escaping this gully, now on rock. It was a traverse across a blank slab via a break only big enough for feet or hands. But having done this the top was in sight.  The southern summit was a tooth 200 feet away, and more importantly the northern summit was higher. To reach the tooth we used a mix of walking gingerly along a snow ridge and squirming across verglassed rock. The tooth itself was a 30 foot climbing-wall-like problem. Standing on top was a great feeling, but not completely satisfying. This was the lower summit; we had to do the northern one as well. We descended towards the north summit on a snow ridge, then after the col headed up and across a face. A final single pitch defeated this summit too. We crammed 4 people onto the tiny northern summit block. Rupert and Ian were still on the southern summit tooth, and we exchanged pleasantries and photos. The clean still air meant we could shout to each other, but it also gave little sense of perspective - the tooth was camouflaged against a different mountain 5 miles behind.

The southern summit was a tooth 200 feet away, and more importantly the northern summit was higher. To reach the tooth we used a mix of walking gingerly along a snow ridge and squirming across verglassed rock. The tooth itself was a 30 foot climbing-wall-like problem. Standing on top was a great feeling, but not completely satisfying. This was the lower summit; we had to do the northern one as well. We descended towards the north summit on a snow ridge, then after the col headed up and across a face. A final single pitch defeated this summit too. We crammed 4 people onto the tiny northern summit block. Rupert and Ian were still on the southern summit tooth, and we exchanged pleasantries and photos. The clean still air meant we could shout to each other, but it also gave little sense of perspective - the tooth was camouflaged against a different mountain 5 miles behind.This truly was a dominating peak, and we had climbed a fine 'ordinary' route - it must have been many notches easier than any other potential line. So to descend, we reversed it, with a single abseil off the southern summit. The final adrenaline shot of the day was descending the secondary glacier. Being self taught skiers, our experience and talents on steep slopes were limited. So, we all adopted a more practical solution - sliding down on our bums. This was such a frequent technique on a previous expedition, that I had made special "bum-sliders" for this use. Basically PVC Nylon 'nappies' that reduced friction, and took the wear off expensive overtrousers. And so we reversed 1˝ hours of uphill skiing in 5 minutes, on our bums, with an ice axe half buried to take some of the speed off and keep us facing downhill. We must have reached speeds of 20mph, with snow pluming up from anything that touched the surface. My bum actually burnt hot after a minute sliding over the hard snow. At the end, I was covered in a thin layer of powder - but who cares, it had saved an hour of knee bashing! [ Top ]

Crevasses. Those gaping, infinitely deep chasms that can swallow you up (or so my mother thinks). Some are, but in my Arctic experience, these are rare. Most are not infinitely deep, the pressures closing them up by about 80 feet down. We crossed many every day, and admired their mysterious blue interiors, so why not take a closer inspection? No doubt "grey-beards" and our insurance company would go berserk at the suggestion, but it still had to be done.

We selected a suitable crevasse, one km from camp and constructed a belay, to abseil in. To start with, the crevasse was wide and open - 50 foot deep, and 20 foot wide, with white walls, and a snow covered solid level floor. We walked along, and down under the first of 3 snow bridges. Snow bridges are more frightening from underneath. These were only 10 feet thick, with 20 foot icicles hung from their undersides like huge daggers. If the bridge collapses while anyone was under it, we'd stand almost zero chance of survival, so with nothing more to loose, I positioned myself directly under an icicle, and stared at it's point - pure danger, there, directly between my eyes. After the 3rd bridge, the crevasse became closed to the surface. Structurally it was now much safer, as the sides closed-in and blue running water ice was all around. But the environment was now completely alien. We descended further into a cave, our crampons (blunted by 6 weeks of mixed climbing) often failed to grip the blue ice. The light was mesmerising. Blue, but not a harsh man-made blue, or even a bright sky blue, but a deep rich blue. Stare directly at bubble free ice, and it draws you in. In the same way people can watch the sea for hours, I could spend hours just staring inside this cave.

We selected a suitable crevasse, one km from camp and constructed a belay, to abseil in. To start with, the crevasse was wide and open - 50 foot deep, and 20 foot wide, with white walls, and a snow covered solid level floor. We walked along, and down under the first of 3 snow bridges. Snow bridges are more frightening from underneath. These were only 10 feet thick, with 20 foot icicles hung from their undersides like huge daggers. If the bridge collapses while anyone was under it, we'd stand almost zero chance of survival, so with nothing more to loose, I positioned myself directly under an icicle, and stared at it's point - pure danger, there, directly between my eyes. After the 3rd bridge, the crevasse became closed to the surface. Structurally it was now much safer, as the sides closed-in and blue running water ice was all around. But the environment was now completely alien. We descended further into a cave, our crampons (blunted by 6 weeks of mixed climbing) often failed to grip the blue ice. The light was mesmerising. Blue, but not a harsh man-made blue, or even a bright sky blue, but a deep rich blue. Stare directly at bubble free ice, and it draws you in. In the same way people can watch the sea for hours, I could spend hours just staring inside this cave.

Being inquisitive creatures at heart, we scrambled on as far as we could get. Now hard ice pressed on both shoulders at once. It was also much darker. Then suddenly the newspaper headline; "2 stupid idiots frozen into glacier" sprang to mind! We turned around and made our way back. [ Top ]

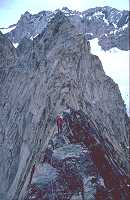

We'd been at our fourth camp for several days. We had climbed the obvious "M" and were less inspired by all the other mountains. I had to pinch myself to remember that every other mountain we could see was stunning, and if was in the UK it would rate alongside the biggest and best. I persuaded Richard to go for a jagged summit to the east of camp. We intended to bag the summit, then attempt a thin looking ridge to the west, making the day a round trip. However, Richard quite rightly pointed out the difficulties on the ridge suggested we should do our route the other way round. Despite being right, I was reluctant - the ridge and especially the final section to the summit looked hard. It would be a fun route after the summit, but having to do the ridge before the summit would raise the stakes. No ridge, no summit. This increased the 'buzz' of the day - continually surveying the route ahead, wondering if we could make it.

We'd been at our fourth camp for several days. We had climbed the obvious "M" and were less inspired by all the other mountains. I had to pinch myself to remember that every other mountain we could see was stunning, and if was in the UK it would rate alongside the biggest and best. I persuaded Richard to go for a jagged summit to the east of camp. We intended to bag the summit, then attempt a thin looking ridge to the west, making the day a round trip. However, Richard quite rightly pointed out the difficulties on the ridge suggested we should do our route the other way round. Despite being right, I was reluctant - the ridge and especially the final section to the summit looked hard. It would be a fun route after the summit, but having to do the ridge before the summit would raise the stakes. No ridge, no summit. This increased the 'buzz' of the day - continually surveying the route ahead, wondering if we could make it.Below the ridge was a steep enclosed north facing cirque, and as we approached, it became obvious the cirque saw little or no sun. The rock was plastered in snow, and below half height, huge icicle covered walls. We started towards a col to the west, that involved the usual snow climbing. This time it was a little steeper, and the route a little thinner. In two places the line disappeared and we put in belays to overcome what felt like Scottish winter problems - loose powder and running water ice abounding. After an hour we emerged at the col and re-met the sun-shine. From here, I could survey the ridge better, but the jury was still out. The crux looked to be the final section to the summit, while the rest of the ridge looked razor sharp, and broken by many difficult and not insubstantial steps. My adrenaline level rose as we changed into rock boots and started moving off. It was now 40 days into the expedition, and our confidence was high. Four weeks earlier, we would have wanted to do the whole ridge in pitches, but now we moved alpine style, moving together and placing protection every 20-30 feet. In my mind, the route involved two major steps and then the summit section. Surprisingly the first step was easier than I had expected. There was then a smooth 'terrace-roof' section (the like of which I have only experienced on the more exciting sections of the Cullin Ridge in Skye). The second step was tough, not technically hard, but steep, very thin, and loose as hell. We put in 2 pitches to over come it, but it shook me. However, now at 2 o'clock, we were having lunch facing the summit. Despite having only one section to go, I was no more certain about whether we would be successful. There was only one possible way to get to the summit, and I was apprehensive. The route was a corner, but the lower part was looked terrible. However all hope was not lost because immediately right of the corner was a vertical wall had a thin crack line up it. Normally I'd have said "no", but these were not normal conditions. This was what it was all about: I was psyched up for a fight, I wasn't about to turn back just like that. It was every bit as tricky as it look - my fore-arms were getting pumped, standing on crystals, finger crimping. "I only climb like this on 30 foot crags" I thought when my concentration momentarily slipped and I became aware of the larger situation. 3000 feet of exposure, 100 miles from anywhere. I overcame the crux on attempt number 4. It was a I-haven't-got-this-far-just-to-fail moment. A single toe jam and a one arm pull for another crack 4 feet above. I don't go in for open displays of emotion when climbing , but this time it just happened: "Yes - YES", I even punched the air. The rest of the day was eclipsed by this moment. After hauling the sacks up, Richard seconded up on a very tight rope. Summit views, chocolate, down climbing, skiing back, tea ... ... I was still living that move on the crux - YES. [ Top ]

So we peak bagged in East Greenland, and saw no one? Not entirely true, Ammassalik is the coastal town near the airstrip, home of our boat man Vittus, and 1500 others, mainly Inuit but also Danes. We didn't visit on the way out preferring to get straight into the mountains, but on our return, we spent 3 days there. Our host was the local Doctor, Hans Christian Florin. It was a fascinating experience - totally different to the rest of the expedition, but it gave a real insight into the culture and problems of the people who live in this land. In western terms, I could see no economic reason for Ammassalik. It didn't seem to produce anything for export, nor was tourism particularly well developed. Yet, there was a well equipped hospital, a police station, supermarket, and stores. And there were plenty of people who appeared to have money to afford the expensive food. It was a puzzling place. A town, with a council, a church, a school, and a hospital, but the Inuit would lived there didn't seem to look like they fitted in. The Danes (who until 1985 governed Greenland) still provide financial support to the settlements - and will have to continue to do so. Without expanding traditional skills (killing small furry animals is too emotive) the local population has lost the ability to be self sufficient. The financial assistance has produced a laisé-faire attitude with little evidence of the entrepreneurial skill. Sadness is my lasting impression of the town - a culture displaced, waiting for nothing. [ Top ]

|

|  |

|  |